Well, y'all, the first episode of the Art(ish) Theory podcast is up which means it is now time for me to write the first ever "Cutting Room Floor" blog post!

The amount of information that comes out of the brainstorming and research for these episodes (and I have brainstormed and researched all of the first season so far) is way more than can fit in a single podcast without it becoming a droning bore. But with each cut I make to the episode scripts, there seems to be a whole lot more I want to say! At first I thought about saving these morsels for another episode down the line—and that might still happen—but the information is so enticing that I decided to simply post them to the blog as a series.

And thankfully for this first episode, there was not as much extra information I wanted to share (which I cannot say for 01.02 and 01.03 coming soon) but it is all still very interesting and helps flesh out the ideas we explored together in Episode 01.01 of the podcast.

To recap, we discussed the question "What is art?", and pushed the boundaries of what we usually mean when we say the word "art." I told a story about how my university Art 201 class became divided over the definition and ended the episode with a list of objects that we do not normally associate with art. If you remember, this list seemed arbitrary, but it went from movie posters to a rock in descending order of how likely we might be to consider that object a piece of art. And right before I got to "twig falling from a tree", I mentioned your toilet.

Some of you might have assumed that I was simply adding a bit of low-brow humor into the mix—which in all fairness, I did find the idea humorous—but it was actually a direct reference to a piece of artwork by Marcel Duchamp called the Fountain, which was as irreverent then as it is today. Fountain is simply a urinal laid on its side and scrawled with a made up name, and its creation and the questions it forced the art world to ask still remain.

THE RISE OF DADA

At the turn of the 20th century, the world had reached the climax of Imperialism. The great powers of the 19th century had formed intricate trade and military alliances that constantly teetered on the edge of collapse. For decades, the world spoke of a coming Great War, and in 1914, an assassination in Eastern Europe quickly drew every major world power into conflict. Over 70 million people would die before the war's end and the political landscape of Europe would be primed for another world war just 20 years later.

From the political turmoil of this period, an art movement formed in Switzerland among refugees and draft dodgers. The artists of this movement saw capitalism, rationality, and blind nationalism as the cause of war and embraced the idea of "nonsense" as a protest against these powerful ideas. These artists saw their work as a necessity, a way to get the middle class out of their complacent apathy toward the war. Poets wrote gibberish, musicians banged on their instruments at random, and artists rejected all forms of objectivity. They called this new style of creative expression "Dada", a near meaningless word that means both "yes, yes" in Romanian and "hobby horse" in French.

The movement was radical—politically and aesthetically—and it spread quickly. Within five years, Dada had found a home in both Paris and New York. While growing in popularity alongside leftist ideologies, the Dadaists gained a wide range of detractors in the art world and society in general who saw their work as dangerous to the social order, which is exactly what the Dadaists desired.

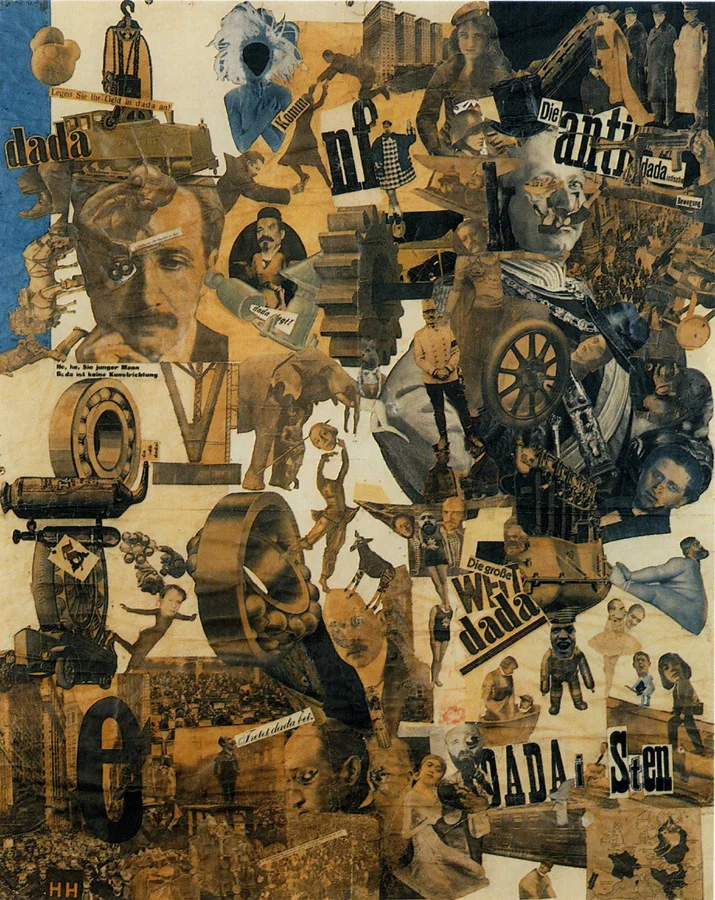

While the Dada movement spanned all of the fine arts, it was in the visual arts that the Dadaists made the most lasting impression. Dada artists expounded on the ideas of the Impressionists and Cubists, taking the idea of abstract to its ultimate conclusion. They used cut pieces of paper, plastic, and photographs to create elaborate, non-objective collages, called photomontages, and cobbled-together sculptures, we now call assemblages, from found pieces of trash and rubble in ways that highlighted the chosen materials' randomness. The Dadaists' desire through all of this was to distance the interpretation of art as much as possible from the technique and skill of the artist.

MARCEL DUCHAMP

In New York City, far away from the fighting and death of World War I, Dadaism embraced a less meaningful tone than its European counterpart. New York Dadaists, mostly refugees from the war, found the vibrancy and freedom of the city to be a stark contrast to what they were escaping in Europe. In response, these artists focused less on their political leanings and more on satire and deconstruction. They found America to be more willing to experiment with the Western ideas of art at the time, and these Dadaists saw themselves wiping the slate clean so a new culture could form after the war.

Marcel Duchamp is perhaps the best known and influential of these refugee artists. Duchamp immigrated to America at the beginning of the war in 1915, but he was no stranger to Americans. He had already caused a stir in the art world with his cubist painting Nude Descending a Staircase, and as he engendered himself to the New York Dadaists, he began to distance himself further and further from the realm of technical skill and focused more and more on the absurd as a form of expression. As he worked with moving assemblages, Duchamp began to see his found materials as art in and of themselves without need of addition. He called these pieces readymades and they were going to make a huge impact on the history of art.

In 1917, Duchamp submitted his most famous readymade, Fountain, to an art show held by the Society of Independent Artists—of which he was on the board—and did so anonymously under the name R. Mutt. After a lot of discussion about whether or not the piece truly was or wasn't art, Fountain was ultimately rejected. The Dadaists responded by publishing a photograph of the piece along with a number of essays and poems in support of the work called The Blind Man. Perhaps the most important argument, and one that would influence submission guidelines to art shows ever since, came from fellow artist Beatrice Wood who wrote:

"Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object."

Though the original piece was lost, (probably discarded into the trash), the impact of Fountain and Marcel Duchamp has endured for over a century, ultimately leaving the question "What is art?" to hang over our heads unanswered forever.